Conserving a Rare Album of William Hogarth Prints

The album of William Hogarth prints was gifted to the Lewis Walpole Library in May 2015 by Richard Greenberg. Detailed below is the journey the album undertook to become a part of the library’s collection and an invaluable resource for scholars and researchers studying William Hogarth.

The Hoadly Folio by Richard Greenberg

Curatorial Considerations by Cynthia Roman

Conservation Treatment by Laura O’Brian Miller

THE HOADLY FOLIO

Richard Greenberg

My wife and I were in London in the Fall of 1988. After a visit to the British Museum, we visited the Print Shops in the area and fell in love with a set of prints of A Rake’s Progress by Hogarth. It was the day before we were returning to New York, and we never made the purchase.

A few weeks later, we passed a print framing shop in Greenwich Village, NY. I went in to ask how they would frame the set. Rather than just quoting on the framing, the owner asked me if I would be interested in purchasing a Hogarth folio that a friend of his was offering for sale that included A Rake’s Progress.

A few weeks later, we passed a print framing shop in Greenwich Village, NY. I went in to ask how they would frame the set. Rather than just quoting on the framing, the owner asked me if I would be interested in purchasing a Hogarth folio that a friend of his was offering for sale that included A Rake’s Progress.

I said yes, and we made an appointment for me to see the folio the next day. When I saw the folio, I loved it. He gave me a price of $6000, and he let me take it home on approval.

I called the Print Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and they were very gracious. When I brought the folio to them, they confirmed that it was real (not a fake or late edition) and they said “quite rare.” I loved it more.

The next day, I went to the framing shop with a check which included New York City sales tax. I didn’t bring the folio with me as there was no way I was going to return it.

All the research that I did led to one name. It was a Professor Ronald Paulson at Yale University. So I called him.

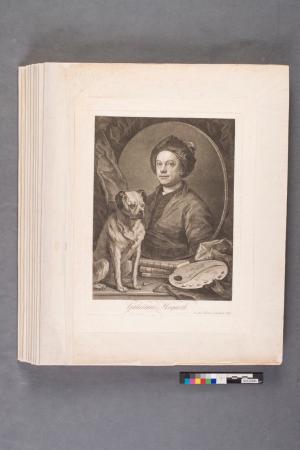

Ron, as always, was very nice and came up to visit my apartment the next time he came to New York City. He was quite excited when he saw the folio and immediately brought up the fact that Bishop Hoadly’s print was the frontispiece rather than Hogarth’s self-portrait.

This was the beginning of a great friendship. Ron’s first job was to talk me out of taking the Rake’s Progress prints out of the folio and framing them. He said that I should not break up this lifetime folio. He subsequently explained that the folio was assembled in 1753 as the last print was Columbus Breaking the Egg. I was told by the print shop owner that the folio came from the vicinity of Winchester – the diocese of Hogarth’s good friend, Bishop Hoadly. For these reasons we thought that it was probable that this folio was made up for Hoadly or a member of his family.

Ron and I have a wonderful friendship. Most recently, he wanted me to protect the integrity of the portfolio by giving it to Yale. Selling the portfolio by auction or private sale would no doubt have put the portfolio in the hands of a dealer who would doubtless break it up by selling individual valuable sets or prints.

I did give it to Yale, and I feel it was a very good decision. Now it is in the hands of a wonderful research group where it will be an important tool forever.

Curatorial Considerations

Cynthia Roman

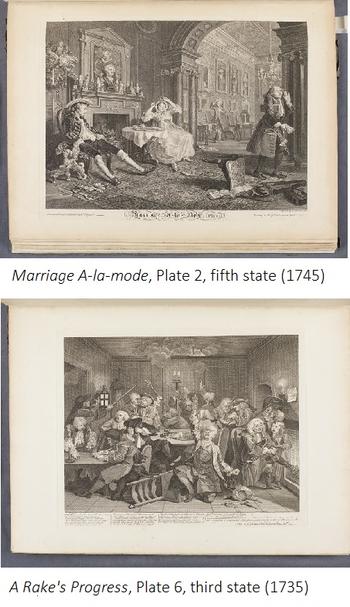

The Lewis Walpole Library has long held the most important collection of prints by eighteenth-century British printmaker William Hogarth in the United States making the library a destination for scholars and students working on Hogarth and related topics. The collection is now made even richer by Richard M. Greenberg’s gift of an early lifetime folio which promises to provide material evidence and insight for scholars and students about important issues of collecting, presentation, and circulation of prints in eighteenth-century England.

The Greenberg folio was likely compiled by Hogarth himself and issued in 1753, the date of the latest print in the volume’s collection. The volume containing sixty-seven prints, including the canonical “modern moral subjects”, and retaining its original boards, is a rare survival. Such folios are often dismantled by dealers or the plain boards used by Hogarth have been replaced by later bindings, and new prints are often added by the collector.

The Greenberg folio was likely compiled by Hogarth himself and issued in 1753, the date of the latest print in the volume’s collection. The volume containing sixty-seven prints, including the canonical “modern moral subjects”, and retaining its original boards, is a rare survival. Such folios are often dismantled by dealers or the plain boards used by Hogarth have been replaced by later bindings, and new prints are often added by the collector.

Mr. Greenberg was introduced to the Lewis Walpole Library by eminent Hogarth scholar Ronald Paulson who served as Professor of English at Yale University from 1975 to 1984 and is now William D. and Robin Mayer Professor Emeritus, Johns Hopkins University. Paulson knew well the W.S. Lewis collection having used it as a significant resource for his authoritative catalogue raisonné Hogarth’s Graphic Works published in three editions (1965, 1970, and 1989). Mr. Greenberg sought Paulson’s opinion following his acquisition of this early intact folio from a dealer in New York City, after which Paulson added an account of this volume to a revised introduction for the third edition Hogarth’s Graphic Works:

There is no doubt that some folios were custom-made for the purchaser, but that the majority were ready-made up; these ordinary editions sold on a fairly large scale, but there were also deluxe editions, supervised by Hogarth himself (or Mrs. Hogarth). For example, a folio in the collection of Richard and Paul Greenberg (NYC) was assembled in 1753; the latest print was Columbus Breaking the Egg without the receipt, therefore after the Analysis was published in December. No prints were added. The first sheet, ordinarily Gulielmus Hogarth, was instead Bishop Hoadly. [Paulson, 1989 p. 19-20].

There is no doubt that some folios were custom-made for the purchaser, but that the majority were ready-made up; these ordinary editions sold on a fairly large scale, but there were also deluxe editions, supervised by Hogarth himself (or Mrs. Hogarth). For example, a folio in the collection of Richard and Paul Greenberg (NYC) was assembled in 1753; the latest print was Columbus Breaking the Egg without the receipt, therefore after the Analysis was published in December. No prints were added. The first sheet, ordinarily Gulielmus Hogarth, was instead Bishop Hoadly. [Paulson, 1989 p. 19-20].

In addition to the unusual placement of the Hoadly portrait as the first print in the volume, Paulson cites a further anomaly in this folio. Along with the states one would expect in 1753 is, unexpectedly, the first state of A Harlot’s Progress published in 1732, although the artist may well have kept some of these earlier prints in stock.

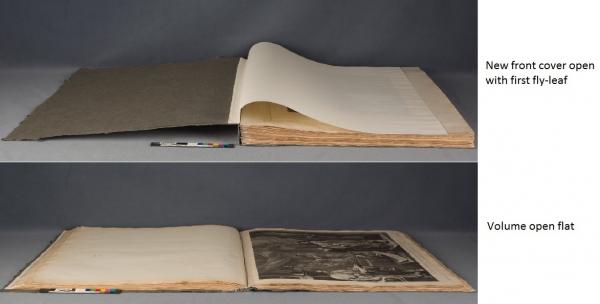

When the folio arrived at the Lewis Walpole Library, the binding was in a deteriorated state and the text blocks were broken into various apparently random bundles or sections, making it nearly impossible to turn the pages and to view the collection as a volume. Keeping the prints together as a folio with pages that could be turned was a significant consideration, and one compelling reason for Professor Paulson to recommend the Lewis Walpole Library as a suitable home for Mr. Greenberg’s folio was to insure it would be preserved as a volume as issued rather than broken up into individual prints. As curator of Prints, Drawings and Paintings, I too was eager to maintain the collection as a bound volume, thus providing students and scholars the opportunity to turn the pages and experience the prints in a folio format as early collectors would have done.

Once the Greenberg gift arrived at the Library, conservation assessments and treatment proposals were explored through discussions with Library Conservator Laura O’Brien Miller to effectively balance the mandates of curatorial stewardship with conservation concerns and treatment options. How could we preserve as much as possible the original state of the folio and at the same time restore it as a functioning volume? The paper boards could not be reused but could be saved. At the same time, the ability to easily remove pages from a new binding for individual exhibition was a curatorially attractive option.

The last puzzle was the unusual order of the pages noted by Paulson whereby the Hoadly portrait, rather than the standard self portrait of the artist, appeared as the first print. During seminars on “The Experimental Prints of James Gillray” and “Collecting the Graphic Work of William Hogarth” in June 2016 at the Lewis Walpole Library, we had occasion to explore this question with a number of scholars of eighteenth-century prints who came for those events. Especially informative was the expert opinion of Hogarth collector and dealer Andrew Edmunds; he had retained notes on the folio from an earlier viewing and had himself observed the variant order. He observed the way in which the glued pages had been divided randomly into sections and suggested that these chunks had likely been reordered during a re-gluing process at some earlier date. A simple re-sequencing of these sections could re-establish an order matching a standard as issued by Hogarth or his widow Jane. Comparisons were made against period inventories at the Lewis Walpole Library and the bound order of other surviving bound collections including the Earl of Effingham’s album at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The order of prints within the individual sections was unaltered from the original.

The critical question for the volume’s treatment was in which order should the prints be bound– the standard made-up order as Hogarth would have issued it or the unique order of the Greenberg folio as we received it? Ultimately, Laura O’Brien Miller devised a flexible solution that could accommodate both options. The fabrication of the new binding allowed us to re-order the sections to present either the sequence beginning with Hogarth’s self portrait of the portrait of Hoadly and also permitted the removal of individual sheets for exhibition.

As the Library continues to develop its programming as a center for eighteenth-century studies with educational opportunities based in its collections, the Greenberg Hogarth folio promises to provide material evidence and insight for scholars and students. In fact, the folio has already been the focus of conversation among scholars, students, and library staff at its inaugural appearance at the seminars on the collecting and connoisseurship of Hogarth prints. The folio will long continue to enable researchers to consider the important issues of collecting, presentation, and circulation of prints in eighteenth-century England.

Conservation Treatment of the Folio

Laura O’Brien Miller

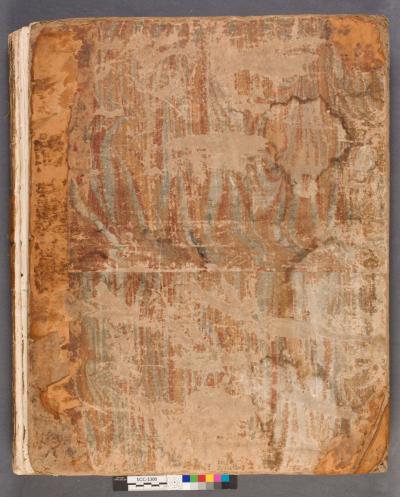

Richard Greenberg’s Hogarth Album (Folio 75 H67 753) is a half-leather folio with marbled paper covers. It is quite large, measuring approximately 23”x18”, with 133 leaves whip-stitched together into bundles.

Upon arrival in conservation, the structure of the folio was documented photographically and in writing, noting both the excellent quality of the paper and prints, as well as the poor condition of the binding. The folio consists of large single leaves, generally with one print on each, whip-stitched together into bundles, minimal sewing between the bundles, and a heavy layer of animal hide glue brushed directly onto the spine holding the bundles together. There is no barrier between the paper of the sections and the adhesive of the spine. The leather was glued directly to the edge of the leaves with no spine lining. Without folds, each leaf is stabbed through by the thread, front to back, leaving large breaks in the paper along the line of sewing holes from use.

The sewing between bundles was weak, with many losses, and very little of the spine leather remained. The boards of the cover were warped, the leather deteriorated and flaking, and there were major losses to the marbled covering paper.

Treatment approaches were discussed in a master class with experts, Sheila O’Connell, former Curator of Prints at The British Museum, Andrew Edmunds, Hogarth collector and dealer, and of course, the Lewis Walpole Library’s Curator of Prints, Drawings & Paintings, Cynthia Roman. Agreed-upon objectives for treatment were the following:

- The prints needed to remain bound.

- The leaves and bundles needed to be bound in manner that would allow flexibility that it could be ordered to reflect either the standard order issued by Hogarth and that in which it came to the library.

- Covers and text block needed to stay together.

- The binding should, ideally, enable the book to be opened flat for viewing, as well as make the removal of individual leaves for future exhibitions possible.

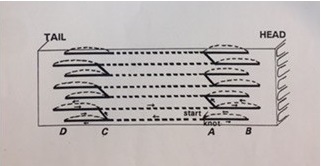

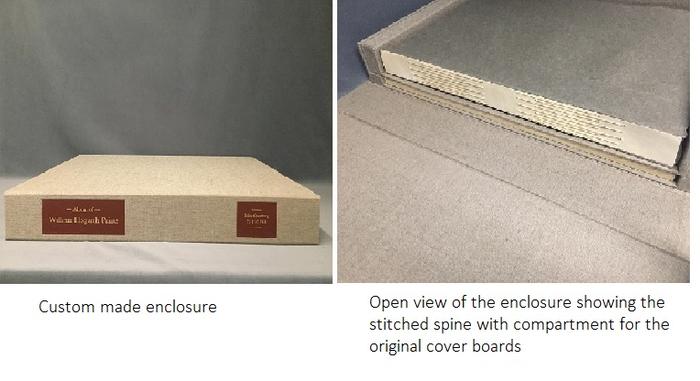

After models of various long-stitch bindings were made and compared, an Italian, staggered, perforated long-stitch sewing structure in a new case was settled on,  because it allowed each bundle to be sewn in independently. The sewing of one section could, therefore, be cut to remove individual bundles, without disturbing the rest. This solution allows for both a complete binding and the removal of single signatures for exhibition.

because it allowed each bundle to be sewn in independently. The sewing of one section could, therefore, be cut to remove individual bundles, without disturbing the rest. This solution allows for both a complete binding and the removal of single signatures for exhibition.

In preparation for binding, the individual leaves were separated, then cleaned and collated, the heavy layer of adhesive on the spine was removed, and tears and losses throughout the text block were mended and filled.

Before the bundles could be recreated, the leaves were guarded into pairs with strips of toned Japanese tissue (see image below). This enabled the pages to open flat. All 133 leaves were guarded into pairs within each section, starting from the center and wrapping one around the next to accommodate the increase in thickness as they made their way to the outside of each bundle. The entire process of guarding each pair into bundles was labor intensive and took several weeks to complete.

Once there were folds to sew through, a jig for the sewing holes was created and holes were pre-punched with an awl.

Once there were folds to sew through, a jig for the sewing holes was created and holes were pre-punched with an awl.

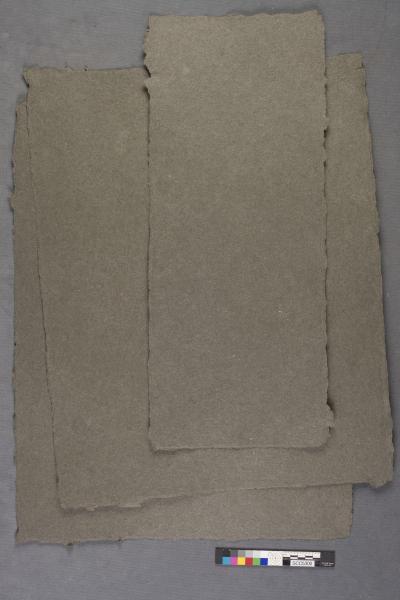

At the same time, the conservator worked with papermaker Amanda Degener to fabricate an appropriate paper for the covers. It needed to be aesthetically attractive, conservationally sound, able to be creased, and take adhesive well, while also being substantial enough to protect such a large and heavy folio. It took a few tries to make something pleasing with all of those qualities, but the result was very satisfactory in the end.

The cover consisted of three sheets of paper: front and back covers, plus a spine piece. Each piece of handmade paper was prepared to fit the exact dimensions of the text book so that the deckle end could be preserved. The spine piece was lined on either side with parchment and an additional strip of paper to support the sewing. Equidistant lines for every bundle were ruled onto the inside of the spine piece to the width of the stack of bundles. Using the same jig for the signatures, cross lines were marked and holes were again pre-punched with an awl before sewing. The remainder of the spine piece wrapped around the text block as flanges for the cover pieces to attach to.

Once the leaves were guarded into bundles, each one was sewn independently through the fold, using waxed linen thread, to the spine piece (see sewing diagram above). Flyleaves were added, front and back, to protect the prints from abrasion, and the cover sheets were attached to the flange of the spine piece with adhesive.

Although, from a conservation perspective, the original cover was too warped and degraded to reuse, from a curatorial perspective it was valuable to preserve this survival together with the re-constructed volume. Delaminated areas of the cover’s boards were reinforced, paper re-adhered, and loose, powdery areas of leather were consolidated. A four-flap folder was then made to house the two boards together. Finally, a customized housing was made for the newly rebound folio with a compartment below for the original covers so the everything could stay together safely.

The donor of the volume, dedicated Hogarth collector and enthusiast Richard Greenberg, had first come to the Lewis Walpole Library to attend the Master Class at which the treatment options for the volume were debated and reviewed with experts. He met with the conservator and the curator in the Yale University Library’s Preservation Laboratory to review the final treatment protocol before it was carried out, and he visited the Conservation and Exhibit Service department again when the treatment of the folio was completed.

In an effort to limit damage and deterioration of the volume, the conservator provided guidelines for its use and care, recommending appropriate environmental conditions for storage and exhibition and articulating proper procedures for handling, packing, and transport.